According to elite neoliberalism, the US and Western Europe today are imperfect meritocracies divided chiefly by race and gender, and not by class. Anyone whose career does not depend on affirming this narrative can see through it. It is obvious that class conflicts have set the North Atlantic world ablaze. But what are the classes?

In The New Class War: Saving Democracy from the Managerial Elite (2020), building on my argument in The Next American Nation (1995), I offered an answer. I proposed that, while the proletariat is still the proletariat, James Burnham, Bruno Rizzi, John Kenneth Galbraith and other thinkers were correct that by the mid-twentieth century power had passed from individual bourgeois business owners to a new ruling class of technocrats or bureaucrats, whose income, wealth, and status is linked to their positions in large, hierarchical organizations, (i.e. nonprofits, government agencies, industrial and financial firms, and so on).

I use the term “overclass” to describe this group. A similar though not identical concept is what is known, after Barbara Ehrenreich, as the “professional-managerial class” (PMC). Whatever terminology you prefer to use, generalizations about all Western elites need to be accompanied by more granular analysis at the level of each country. Referring only to the US, I think it is helpful to go beyond the basic distinction between the overclass and the working class and identify distinct groups within each.

Only the most primitive Marxists believe that a tiny group of individual capitalists—to the manor born or self-made—controls societies from behind the scenes.

The managerial elite proper consists of the functionaries of corporations, large investment banks, law firms, government agencies: both civilian and military, nonprofits, and universities. They may have professional degrees, but they are essentially organization men and women in centralized, hierarchical, bureaucratic entities. They are the chief beneficiaries of the neoliberal system set up in the last half century to replace the New Deal order.

But the American elite includes three other groups in addition to these bureaucratic managers. One consists of hereditary rentiers—heirs and heiresses born into rich families. Old money types should be distinguished from tycoons like Bill Gates or Jeff Bezos, who tend to be products of upper-middle-class or modestly rich families who happened to become incredibly rich. Only the most primitive Marxists believe that a tiny group of individual capitalists—to the manor born or self-made—controls modern societies from behind the scenes. I will not pay further attention to old money in this essay.

In German a distinction has long been made between the Besitzbürgertum (propertied bourgeoisie) and the Bildungsbürgertum (educated bourgeoisie). The equivalents of these two groups exist in the US today. They are distinct from the big-organization managers and important in American politics out of all proportion to their numbers. Lumping them together as “PMC” confuses matters. Let us call them the professional bourgeoisie and the small business bourgeoisie, instead.

The professional bourgeoisie—made up of lawyers, doctors, professors, K-12 teachers, journalists, nonprofit workers, and many of the clergy—is concentrated in the teaching, helping, and research sectors. Their jobs often pay modestly but provide both status and a degree of personal autonomy that the frequently better-paid managerial functionaries in more hierarchical occupations do not possess.

The small business bourgeoisie consists of the owner-operators of small businesses and franchises, along with genuine contractors (as opposed to proletarian “gig workers”), who are either self-employed or employ others.

In the United States (if not necessarily other Western countries), the overclass can be viewed as a compound of the classic managerial elite, plus these two bourgeois classes. A four-year college diploma is a prerequisite for entry into all of these elite groups, except for the small business bourgeoisie, which includes a few individuals who become prosperous without attending a university.

The working class in the US is divided as well. First, there is the heartland working class—those who work in the industries located in the low-density exurban heartland. These industries include manufacturing, agriculture, energy, retail distribution, and warehousing.

And then there is the hub-city working class. This class of workers can be found in metropolises like New York, San Francisco, Atlanta, and Houston. Many of these members work directly for the urban overclass as maids, nannies and other domestic staff, or otherwise indirectly in luxury services that cater to the affluent elite.

(A note: by the “heartland working class” I do not mean the stereotypical “white working class.” Most African-Americans and Hispanics are high-school-educated workers who live and work in suburbs and exurbs. Those areas also contain many foreign-born workers, though first-generation immigrants make up a greater share of the populations of hub cities.)

To the distinct hub and heartland working classes can be added a third non-elite group, often described as the lumpenproletariat—or, perhaps more clearly, the “underclass.” (In the 1990s the speech police of the politically-correct left banned the use of “underclass” from academic and journalistic usage in the US, but the term is neither racist nor an insult.) This refers to members of often-broken families caught in multigenerational poverty, particularly those trapped in the grim carceral subculture of public housing, food stamps, petty crime, and the prison-industrial complex. Like the hub and heartland working classes, the multigenerational underclass is racially and ethnically diverse, and found in both urban and rural parts of the US.

The reader who has followed me to this point will be relieved to learn that my taxonomy includes only these six categories: three within the broadly defined overclass (the managerial elite, the professional bourgeoisie and the small business bourgeoisie) and three within the broadly defined working class (the hub city working class, the heartland working class, and the underclass).

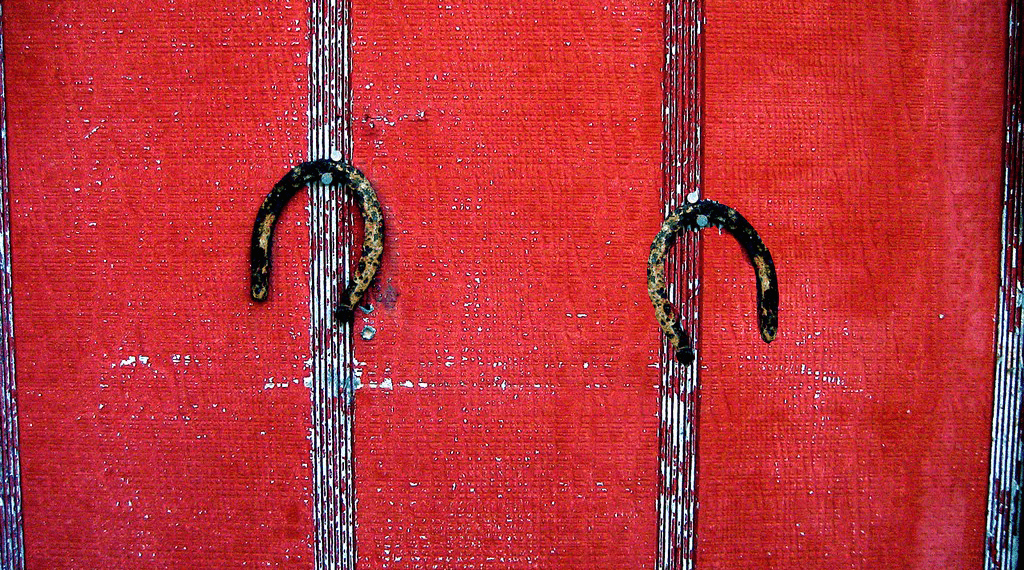

Since this is all very abstract, an image might help. Visualize two horseshoes—a lower horseshoe whose two prongs point up, and an upper horseshoe whose two prongs point down. The lower horseshoe has the underclass at the bottom/midpoint and the hub city working class and the heartland working class as the points of its two opposing prongs. The upper horseshoe has the managerial elite proper as its midpoint/apex and the professional bourgeoisie and the small business bourgeoisie as the points of its two opposing prongs. Arranged in this way, the two horseshoes form a rough outline of a circle, with the managerial elite at the very top, the underclass at the very bottom, and the two working classes and the two bourgeoisies distributed in between.

The individual makeup of the two horseshoes are not equal in number. By the broadest definition of membership in the overclass—possession of a four-year college degree, plus a few affluent high-school-educated contractors or business owners—the upper horseshoe includes no more than a third of the US population.

American politics is little more than the internal politics of the overclass, now that the working-class majority has lost the grassroots, mass-membership institutions that once gave it collective bargaining power—private sector trade unions, influential religious organizations, and local political parties. Members of the working-class majority play no role except as occasional voters. They tend to be ignored, except during election seasons, when they are targeted by manipulative appeals based on race and gender in the case of the Democrats and religion and patriotism in the case of the Republicans.

Both DSA progressivism and Tea Party conservatism are different strategies to stave off the proletarianization of their bourgeois constituents.

Let us focus, then, on the three overclass factions of the upper horseshoe. The present system serves the credentialed elite in the large private, public, and nonprofit bureaucracies of the managerial elite quite well. In contrast, the members of the professional bourgeoisie and the small business bourgeoisie live in terror of proletarianization. Many professionals fear they will not be able to secure high-status jobs with their educational credentials, and the small proprietors fear they will lose their businesses and be compelled to work for others.

At the risk of being overly schematic I would suggest that the “center,” “left” and “right” of America’s top-thirty-percent politics can be mapped imperfectly onto the managerial elite, the professional bourgeoisie and the small business bourgeoisie. In particular, both DSA progressivism and Tea Party conservatism can be understood as different strategies for enlisting the power of government to stave off the proletarianization of the constituents of the two bourgeoisies.

The goal of so-called progressivism in 2020s America is to expand employment opportunities for college-educated, center-left professionals, while adding new wings to the welfare state that are tailored to their personal needs. The slogan “Defund the police” is interpreted by the bourgeois professional left to mean transferring tax revenues from police officers, who are mostly unionized but not college-educated, to social service and nonprofit professionals, who are mostly college-educated but not unionized. The enactment of proposals for free college education and college debt forgiveness would disproportionately benefit the professional bourgeoisie, not the working-class majority whose education ends with high school. Likewise, public funding for universal day-care allows both parties in a two-earner professional couple to maximize their individual incomes and individual career achievements by outsourcing the care of their children to a mostly-female, less well-paid workforce at taxpayer expense.

It is no coincidence that many professionals in the sectors most dependent on their funding on donations from the capricious rich, like philanthropy, colleges and universities, and the media, hate billionaires with the passionate resentment that is reserved for benefactors. In their view, in a just society, the arts program or the NGO would be permanently funded by tax revenues, instead of annual fund-raising appeals to this or that plutocrat’s personal fortune or foundation.

Gore Vidal was known to say that America has socialism for the rich and free enterprise for the poor. Contemporary American progressivism can be succinctly described as social democracy for the professional class.

While the professional bourgeoisie, based in the public sector, universities and nonprofits, is the social base of progressivism, the social base of conservatism is the small business bourgeoisie, particularly those in this group who are native, white and suburban or exurban, as opposed to immigrants who run small businesses. Like the professional bourgeoisie, the proprietarian bourgeoisie wants to enlist the power of the state to protect its members from proletarianization.

To avoid being squeezed out of existence between big business and organized labor, the small business bourgeoisie has fought for generations on two fronts, demanding subsidies and exemptions from government regulations, while insisting on anti-union and anti-labor legislation and a reliable supply of cheap labor (preferably guest workers or illegal immigrants who cannot vote). The lobbies for the small business sector naturally oppose any “decommodifying” social insurance reforms. Examples are longer periods for unemployment insurance or universal health care, each of which can increase the bargaining power even of non-unionized workers by allowing them to hold out longer until employers are forced to make better offers.

The upper horseshoe schema explains American political factions in terms of different combinations of its elements. When the professional bourgeoisie allies itself with the Managerial Elite, you get Clinton-Obama-Biden left-neoliberalism. When the small business bourgeoisie allies itself with the Managerial Elite, you get George W. Bush-Paul Ryan-Nikki Haley right-neoliberalism.

When the professional bourgeoisie and the small business bourgeoisie unite with each other against the oligopolies and monopolies that dominate modern industry and finance and the managers who run them, you get the neo-Brandeisian, small-is-beautiful antitrust school. Their anachronistic small-producerist ideal, in which everything big has been broken up by government antitrust litigation, is an economy of small shops, artisanal craft breweries and independent doctors and lawyers.

In addition to clarifying the constituencies and goals of contemporary American political factions, the double horseshoe theory helps explains what might be called “the two reopenings” during the COVID-19 pandemic, between March 2020 and July 2020.

The protests associated with the first reopening were led during the early stages of the lockdown by conservative members of the small business bourgeoisie. Many of their undercapitalized storefront businesses, like hair salons, and restaurants, and car repair shops, were threatened or wiped out by city and state shut-down orders. The protests were dominated by petty-bourgeois business owners, and not their low-paid employees—some of whom might have been endangered by a premature return to their workplaces during the pandemic.

The initial response of the progressive professional bourgeoisie was to ridicule and denounce the right-wingers for endangering their own lives and those of others by ignoring the advice of credentialed public health experts.

Then, during the protests that followed the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers, the same progressive professional bourgeoisie concluded that systemic racism was a greater threat to public health than COVID-19, which—mirabile dictu!—cannot be spread at left-wing demonstrations.

I am not the first to observe that what were initially legitimate protests against the use of excess force and racism by particular police departments have turned into a campaign for greater funding for social-services jobs and diversity officer jobs for members of the professional bourgeoisie in their twenties and thirties.

What does all of this mean for the neglected working-class majority on the sidelines of American politics? A century ago, trade unionists like Samuel Gompers and socialists like Eugene Debs criticized antitrust and praised large industrial combinations, on the sensible grounds that large, modern corporations are easier to unionize and/or socialize than lots of small businesses.

A case can be made that both the professional bourgeoisie and the small business bourgeoisie are relics of an earlier techno-economic paradigm. Each is a leftover pocket of technological backwardness and labor exploitation in an advanced industrial economy.

In American higher education, a dwindling minority of tenured academics, using pedagogical methods unchanged from the agrarian era, lords it over a mass of impoverished guild apprentices, the poorly-paid, insecure, non-unionized adjuncts who now teach most university students nationwide. At the same time, the business models of many small, owner-operated firms in the US are made possible by poor-country levels of worker rights and social insurance—and much of the workforce consists of recent, desperate immigrants from actual poor countries. Because the backward professional and small business sectors have much lower productivity than the rationalized, capital-intensive parts of the economy like manufacturing and energy, they pay low wages to much of their workforces while charging high prices to consumers.

Needless to say, any new cross-class settlement would have to follow the recreation of powerful mass-membership working-class organizations in current and newly-rationalized, sectors, which would permit the transformation of the majority of Americans in the bottom horseshoe into subjects, not mere objects, of American politics. But that is a story for another day.