In April 2006, American comedian Stephen Colbert provided the feature performance for the White House Correspondents’ Dinner, the annual schmoozefest of Washington media elites. Despite the initial controversy incited by Colbert’s predictable liberal jabs at the Bush administration and the press, most of his routine has subsequently faded from collective memory, a consequence of an amnestic political culture ever-fixated on the new. However, there exists a single phrase from his speech that has demonstrated a curious staying power, perhaps due to its pithy encapsulation of the American liberal worldview. “Reality,” Colbert quips, “has a well-known liberal bias.”

The belief that one’s political ideology provides accurate models of the world and human societies is certainly not exclusive to American liberals. Traditionalists, libertarians, Marxists: most everyone intellectually invested in their politics trusts their worldview to be the correct one. What distinguishes Colbert’s claim is its supposed empirical basis, as reflected by the fact checks and think tank statistics of establishment liberal institutions like The Washington Post and the Center for American Progress. Statements like “evolution is real” and “the Iraq War has become too costly and destructive” were emblematic of this type of early aughts, “common sense” liberalism, wherein reality itself seemed ever-elusive to Bush era conservatives, oftentimes envisioned as blind to the facts due to their corruption or duncery.

In the intervening years, this smug, simplistic epistemology has evolved and diverged, given distinct expressions by television pundits and new media personalities on both sides of the aisle. The general sense that a proper interpretation of all the relevant facts validates one’s policy positions has become ubiquitous throughout the political mainstream and consequently featured more prominently within political discourse. Every new study produced by the Brookings Institution now entails a suite of explainer articles from online publications. Fact checking websites and newspaper features have proliferated unimpeded.

But the metastasis of this shallow empiricism is merely the tail end of something far larger and more ruinous. The collapse of politics into entertainment and hobbyism—a decades-long process brought about by the expansive commodification and social staticism of the neoliberal era—has transformed political commentary and analysis into a market of niche consumer products, each aimed at a specific ideological demographic. Whether it’s an opinion article in their preferred partisan magazine or a YouTube video by their favorite policy analyst, Americans now growingly consume political products in which the validation of their views is an essential feature. Although publications and think tanks have been churning out partisan opinion pieces and policy research since the beginning of the eighteenth and twentieth centuries respectively, the total commodification of political discourse over the past five decades has engendered drastic qualitative changes to these practices. Thoughtful, extended prose cannot quickly satiate the consumer’s desire to feel clever and correct, so the monadic fact, the easily citable study, and the repeatable line of argumentation have become king. Detail, elaboration, and nuance are usually seen as affected or unnecessary protuberances; a raw sense of political superiority is ultimately what’s being sold. Who, after all, doesn’t want to believe reality is biased in their favor?

The leftism promoted by people like Matt Bruenig and Bhaskar Sunkara is little more than a set of corporate regulations and New Deal-esque social programs for the twenty-first century accompanied by the winking promise of bigger and better changes to come.

For the neoconservative right, this tendency is manifested most purely in videos of Ben Shapiro relying on “facts and logic” to rhetorically rip apart the arguments of naive college students. For the neoliberal left, it can be seen in smirking correspondents from The Daily Show interviewing “simple-minded” Trump supporters. A century ago, the politically-engaged college student might have cited someone like Walter Lippmann—whose dense writings on journalism and mass democracy remain incredibly influential—as a formative intellectual influence. The politically-engaged college student of today, however, is more likely to reference someone like conservative activist Charlie Kirk or liberal Twitch streamer Destiny.

These observations might seem banal to many self-described socialists. Mainstream political commentary is regularly—and rightly—criticized as consumerist, intellectually bankrupt, and pro-status quo by those on the left. And over the past decade or so, this type of oppositional, anti-capitalist discourse has become markedly more prevalent as a new contingent of young socialists, drawing upon the populist energy generated by the Occupy movement and the unsuccessful presidential bids of Bernie Sanders, has gained increasing prominence.

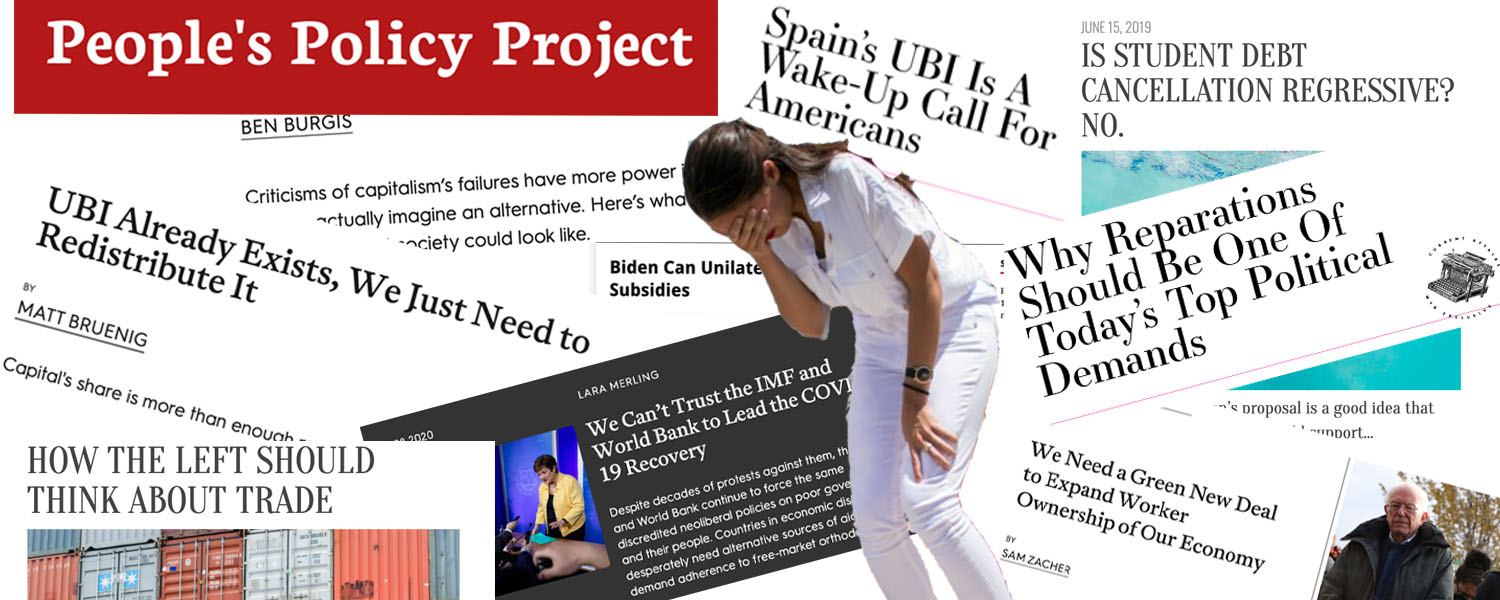

Even though some of this millennial anti-capitalism has even managed to inch its way into the fringes of mainstream publications and news outlets. Its real strength, however, lies internally. Clustered within organizations like Jacobin, People’s Policy Project, and Current Affairs, the burgeoning millennial left has carved out a comfortable little niche for itself in attacks on Republican and Democratic inadequacies and lamentations over the disempowerment of the working class. Such denunciations of neoliberalism are currently in vogue. But in its nominal opposition to capitalism and criticism of the mainstream, this nascent left has tacitly (and erroneously) assumed it is beyond the reach of the insular neoliberal consumerism it so loves to lampoon. A parochial, wonkish, and reformist vision of socialism, marketed towards a rather specific socioeconomic demographic, has consequently come to define it.

In Capitalist Realism, British cultural theorist Mark Fisher argues that as neoliberalism has crushed all possibilities for social transformation in the real world, our political imaginations have capitulated to its terms. According to him, capitalist realism is best understood as “the widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to it.” Indeed, although neoliberalism’s pernicious austerity and hollowing out of civil society have been destructive, its steepest consequences may be ideological.

The book’s second chapter explains how this “capitalist realism” has reshaped the theoretical outlook of the anti-capitalist left. Fisher writes, “Since it was unable to posit a coherent alternative political-economic model to capitalism, the suspicion was that the actual aim was not to replace capitalism but to mitigate its worst excesses…” Talk of agitation and intransigence has almost completely subsided. Despite the guarded optimism of the anti-capitalist commentariat, ostensibly radical and decentralized movements like Black Lives Matter have been thoroughly institutionalized by the left-wing of capital through nonprofits and advocacy organizations and integrated into the Democratic Party. Occasional flashpoints trigger mass protests that soon dissipate notwithstanding the rhapsodies of their transformative potentialities. The prospects of a bottom-up overthrow of the capitalist state being laughably non-existent for the foreseeable future, many of the millennial left’s leading lights have turned toward capitalist liberal democracy so that they might retain some sense of optimism. Notionally, they hope to reform their way to “socialism” through electoral victories and an empowered working class. In practice, they merely seek to reduce the harms imposed by capitalist domination upon the downwardly-mobile petty bourgeoisie.

The negligible socialism that has clawed its way to a marginal niche in mainstream political discourse is, overwhelmingly, of this reformist variety. It is the leftism promoted by people like Matt Bruenig, Nathan Robinson, and Bhaskar Sunkara, little more than a set of corporate regulations and New Deal-esque social programs for the twenty-first century accompanied by the winking promise of bigger and better changes to come.

With attention focused on bourgeois liberal democracy, electoral outcomes and deliberation on issues of state administration take center stage. The preeminent matter of building power, originally a question of how best to radicalize and organize the working class, devolves into the mind-numbing dilemma of whether American socialists should attempt to push the Democratic Party to the left or compete in elections with their own independent party. Working-class organization becomes a secondary concern, a means for putting nominally socialist politicians into office who will then allegedly act on behalf of the downtrodden.

In our current neoliberal context, electoral politics is perhaps the only sphere of society that contains at least a modicum of contestation and political activity, dominated, though it is, by bourgeois interests. This singularity is part of what makes it so seductive. Although millennial socialists would be loath to admit it, their fantasies of concrete class struggle in the workplace and in the streets are just that: fantasies. American labor has been in retreat for decades now and, as Antoine Sebastiani has so persuasively argued, the dusty rank-and-file organizing strategy that they wish to resurrect stands little chance of revitalizing it. With substantive class struggle off the table, millennial socialists are left with empty gestures towards a bygone era of organized labor and an electoral politics that has long been distant from most proletarians and their needs.

Neoliberal revanchism has almost wholly depoliticized contemporary proletarians. Alienated from a system that willfully ignores their suffering and then shames them for not wanting to participate in it, they are understandably disaffected. The shrill political agency of the millennial socialist cohort is therefore made possible by its non-working class character. Socioeconomically precarious members of the professional-managerial class, the overeducated and underpaid, are its target demographic.

Millennial socialists favor a dressed-up post-Keynesian economics, throwing in a meaningless fetish for worker co-ops to maintain their radical credentials.

Instead of representing a radical reordering of society with the oppressed at the helm, the rhetoric and policy priorities of millennial socialists reflect a desire for the capitalist state to subsidize the middle-class lifestyles falsely promised to them when they enrolled for a four-year degree. Though the decaying American Dream has produced many young people who define their politics through economic angst and discontent, it has not yet undermined their shrugging acceptance of bourgeois democratic institutions instilled by higher education and the pervasion of neoliberal ideology. Their primary goal is thus the renegotiation of the size of the welfare state.

Socialist publications and policy analysts have sprung up to both aid in the grand ideological battle and feed the political hobbyism of this left-leaning petty bourgeoisie. Much emphasis is placed upon making socialism palatable to liberals, a commitment to the battle of ideas of the commodified public sphere. Analyses of mass consumerism and the value form are consequently reduced to nonsense espoused by “less pragmatic” Marxists. Millennial socialists instead tend to favor a dressed-up post-Keynesian economics, throwing in a meaningless fetish for worker co-ops to maintain their radical credentials.

In essence, they seek bourgeois democratic respectability through imitation of the political mainstream and a devotion to wonkishness. Though they currently hold little influence within halls of power, millennial socialists emulate the apparati of think tanks and publications that buttress the Republican and Democratic parties in the hopes that one day they might be able to push their way in. The Marxist critique of the administered society is subsequently replaced by the “market socialist” policy proposal. Studies and statistics on social programs supplant an emphasis on totality. Articles on the successes of self-styled socialists abroad and the deficiencies of policymaking at home come to dominate the Twitter feeds of the left PMC. Solutions to the student debt crisis, ruminations on reparations, and explanations of socialist UBI schemes permeate the homepages of Jacobin, People’s Policy Project, and Current Affairs, occasionally interrupted by the obligatory birthday homage to a long dead Marxist or the odd interview with a lefty academic.

A few months of frequenting these sites and one will notice the same topics and arguments recycled ad nauseam, perennially emphasizing the possibilities within electoral politics; essays dissenting from this orthodoxy are seldomly published. If, like most educated Americans, your primary concerns are top-down state policy and the contours of capitalist democracy, there exists plenty of “anti-capitalist” content available for consumption.

But this incessant policy writing ultimately precludes a truly radical anti-capitalism. In presupposing the capitalist state and centering short-term political possibilities, millennial socialists are forever forced to moderate their politics. Their proposals must be “economically feasible” and “efficient” and cannot, under any circumstance, exhaust the state coffers. A great deal of effort is put into demonstrating precisely how taxation will work, how monies and personnel will be distributed by the bureaucratic apparatus, and how alike these proposals are to policies of the New Deal, and Great Society eras. These precedents—usually established explicitly—are what reveal the true nature of the millennial socialist project: a slightly beefier take on capitalist social democracy. It is assistance meant for a middle class squeezed by neoliberalism.

Despite its constant condemnations of neoliberalism, millennial socialism has tragically fallen victim to the apodictics of neoliberalism’s order of reason. It regularly justifies itself through metrics of economic feasibility and grovelingly demonstrates how its welfare policies will better secure the consumptive habits of the middle and working classes. While it may, on occasion, complain about the destruction wrought by the under-regulated profit-maximizing firm, it is not, at its core, in favor of the firm’s abolition. At most, it advocates for the greater socialization of profit. For these reasons, millennial socialists cannot meaningfully challenge capitalist hegemony; their politics, rather than representing a critique of capitalism’s conceptual mystifications and contradictions, instead rely on their continued reification.

Insofar as it is unable to extricate itself from capital, millennial socialism does stand a chance of seeing some of its preferred policies implemented in the oncoming decades. Any revolutionary potentialities engendered by material bereftness will be neutralized through welfare policies that ensure a meager subsistence or co-opted by the organizational apparatus of millennial socialism. But in the interim, with only a handful of sympathetic politicians scattered in legislatures throughout the country, millennial socialism functions more as a consumer product than it does a real political movement. It is progressive liberalism with a red aesthetic, a set of media outlets and talking heads that seeks to satisfy the desires of the left PMC to feel intelligent and informed. While their finance bro friends page through The Economist, the Columbia grad student peruses the front page of Jacobin. It is leftism as cultural signifier.

This form of socialism—parochial, wonkish, and lacking self-awareness—is nothing new or innovative. Marx himself criticized an earlier incarnation of this tendency as “bourgeois socialism” in the third chapter of The Communist Manifesto. Hoping to end class antagonisms and preserve bourgeois society through the narrow economic betterment of the proletariat, “The Socialistic bourgeois want all the advantages of modern social conditions without the struggles and dangers necessarily resulting therefrom… They wish for a bourgeoisie without a proletariat.” How wonderfully timeless. It would indeed seem that all historical personages and events—including bourgeois socialism—appear, as it were, [more than] twice.

This dominant mode of anti-capitalist thought must be torn asunder if a notion of a “better world” is to be rescued from neoliberal ideological hegemony. It is a mode of thought currently alienated from the working class and its interests and it serves as little more than a consumer product for educated “radicals” who wish to feel themselves clever. Organizationally in disarray and with little hope for substantive change in the foreseeable future, anti-capitalists can only rely on their clarity of thought for the time being. Commitment to exposing theoretical missteps is therefore of the utmost import, for before we take the world, we must first retake our political imaginations.