Although she had little medical training, Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes claimed that she invented a foolproof way to test blood using a single drop. Drawing on her connections to wealthy and powerful elites, Holmes was able to raise millions of dollars and attract a lot of media hype. The problem: Theranos’ blood-testing technology didn’t actually work. But Holmes’ fraud wasn’t discovered until she’d already built a $9 billion empire.

Holmes isn’t the only charlatan peddling miracle cures. Enter diversity trainer and education scholar Robin DiAngelo, who is offering a simplistic remedy for racism via her book White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism.

Although DiAngelo’s book was published in 2018, it is currently at the top of the New York Times’s list of best-selling nonfiction books. News articles and social media are filled with mentions of the book’s popularity and the appeal of White Fragility among white people seeking to understand the premise that racist beliefs and practices were not eliminated by the abolition of slavery or the election of a black president.

The solutions presented in White Fragility are based on the premise that white people have not built up their “racial stamina” because they rarely experience “racial discomfort.” When confronted with the claim that they are white and therefore receive privileges based on their skin color, they allegedly respond with a range of emotions, including fear and guilt, as well as behaviors “such as argumentation, silence, and withdrawal from the stress-inducing situation.” Thus, white fragility is defined as a way for white people to protect themselves from conversations that could pose a risk to their personal identity and unearned advantages.

DiAngelo claims that she developed this theory while working as a diversity trainer for various firms. She notes that she was puzzled by employees’ resentment and disinterest in learning more about racism at mandatory trainings because there were few—if any—people of color amongst them. She was also surprised that they didn’t seem excited to learn from non-white co-facilitators prepared to educate them about race.

What becomes clear after getting past the introduction is that White Fragility is really an expression of DiAngelo’s own guilt and fear about her contradictory role as a Euro-American racial dialogue manager: she gets paid to be an expert on race and racism despite the fact that she believes that white folks can never be experts on race and racism. Regardless of why Diangelo wrote the book, if our goal is to address racism and inequality in ways that serve the interests of poor and working people, then there are many reasons to be worried about White Fragility’s popularity.

To begin with, DiAngelo views racism as a problem to be combated with sensitivity training. The premise of diversity and cultural competency training is that by educating European-Americans on the persistence and consequences of racism, they can be transformed into non-racist (or, ideally, anti-racist) individuals.

But diversity training has been shown to be a largely ineffective way to address racism in American workplaces. These lectures and workshops do little—if anything—in the way of addressing the structural tensions that workers must navigate on a daily basis. As Frank Dobbin has noted in his book Inventing Equal Opportunity, such training is often merely a clever way of establishing legal protections for firms facing accusations of discrimination. Studies have also shown that such diversity training can actually activate and reinforce biases. It is no wonder DiAngelo had to explain why corporate employees under her tutelage react to her the same way high school students react to a substitute teacher.

White Fragility also reinforces the belief that the responsibility for racism lies with individual workers’ attitudes and invisible phenomena including implicit bias rather than the policies and practices authorized by employers. If I were an employer, why wouldn’t I want to hire a specialist to train workers to believe that their own identities and unconscious biases are the main sources of inequality, instead of exploitative workplace practices? Simply put, DiAngelo continues to be paid by schools and firms across the country for the same reason that employers pay any professional or manager: it advances their material interests as opposed to the interests of their personnel.

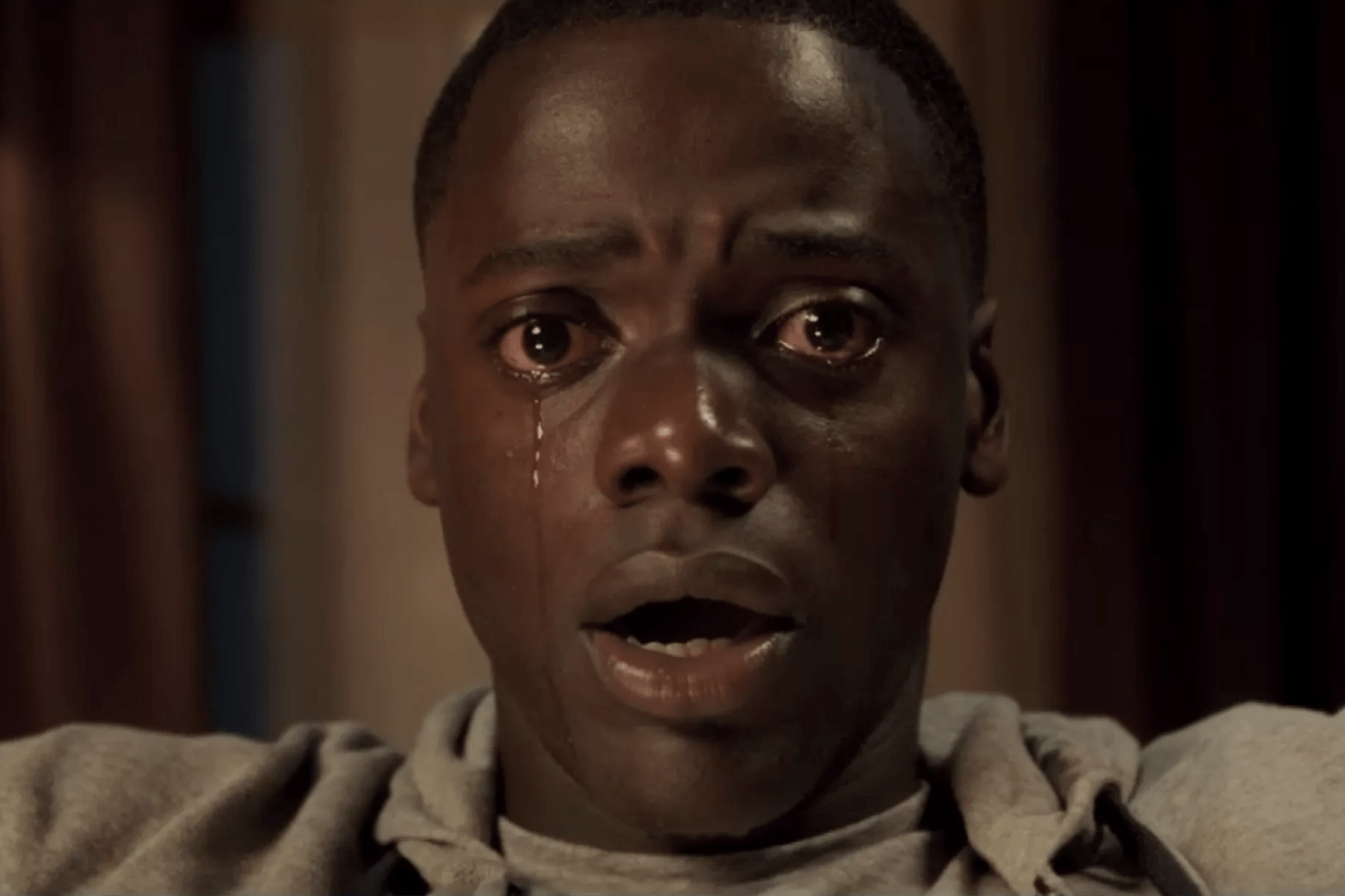

There’s a more essential problem at play here: White Fragility actually reinforces racist beliefs. Sociologists generally agree with the notion that ethnicity can refer to an identity that individuals or communities assert, but races are labels that are ascribed to individuals. As scholars like Barbara E. Fields, Adolph Reed Jr., and, amusingly, DiAngelo’s fellow-traveler Ibram Kendi, have repeatedly noted, racist beliefs and practices presume and reify the belief that nature produced different types of humans with unique, inborn attributes. DiAngelo doesn’t talk about supposed “racial” differences in skulls or intellectual capacity, but the book is filled with associations of race with physiological differences. Terms such as racial stress, racial [dis]comfort, racial control, racial knowledge, the unavoidable dynamics of racism, racial relaxation, and racial manipulation disturbingly resemble inverted beliefs communicated by white nationalists and commodified by the Armitage family in the film “Get Out.”

I do not believe that DiAngelo is racist. But anyone claiming to be an expert on the sociology of race and racism should recognize the consequences when associating physical characteristics with racial differences. No matter how many times she confidently claims that “as a sociologist [but not really], I’m quite comfortable making generalizations [without deploying sociological methods],” racial essentialism is racial essentialism. And unlike DiAngelo, my family and I are incredibly vulnerable when police officers, politicians, educators, doctors, lawyers, and other folks with power act upon this brand of racial essentialism.

The popularity of White Fragility does suggest that many people view the recent protests as a sign that they should understand and address the invidious treatment of people who are not labeled white. But it offers nothing to address the structures undergirding systemic racism within political and economic institutions or the dramatic decline in state funding for social programs in recent decades. Nor can it speak to the coronavirus pandemic that has resulted in more than 8.8 million cases and at least 465,000 deaths worldwide, according to the W.H.O.’s latest data, and the paltry form of federal relief for the poor and working-class citizens affected by the crisis, with more than 40 million people unemployed as a result of the current crisis.

Despite knowing full well that the current demonstrations probably won’t end police brutality and racism, I have maintained hope that there might be some benefit for its victims at the end of the day. Maybe, just maybe, we will live in a nation where claims of racism are taken seriously. At the very least, I hope the demonstrations can ensure that as an African-American, I will no longer be afraid whenever I see blue and red lights flashing in my rear-view mirror, or that police officers won’t automatically assume I am a criminal who deserves to be assaulted or killed without consequence.

But if we allow White Fragility and similar works to become the handbooks for addressing these injustices, there will be zero meaningful progress to speak of—at least for those of us who aren’t killed by officers trained to recognize their “racial stress.”