Probably nothing has driven home the spuriousness of American democracy better than the chronic failure of liberals to represent the interests of the nation’s poor and working class, the base they allegedly represent. The success of the financial elite while supported by various liberal governments had forced observers to repeal the default consensus that liberals were simply ineffectual. In the wake of Occupy, the working interpretation lurched forward to something like “paid to lose.”

But it sounds like circular reasoning to explain liberals’ renunciation of the public interest as simply a result of neoliberalism pressing out a different sort of liberal—the flag-lapelled and fiscally-spooked type. A more instructive story is revealed by studying their formative moves from the late-1930s to the early-1940s. This period helps contextualize liberal relationships to both power and democracy in a stream of historical echoes that connect with our present. Here, beneath these depressingly familiar refrains, lie the earliest strata of liberal surrender.

The Original “Excess of Democracy”

While it may seem ironic that overwhelming popular support for early New Deal policies would, in time, lead to misgivings in many of its liberal champions, that’s exactly what happened. In his book, Lords of the Press, legendary newspaperman George Seldes notes that “in 1937… a change seemed to come over the liberal viewpoint of the New York Post.” At the time, the paper was the most left-leaning of the large New York dailies, and its publisher, J. David Stern, had been a stalwart liberal for decades.

Seldes argues that the Post “deliberately set out to drive the extreme left wing out of its ranks” when it editorialized that “the ‘united front’—union of liberals with Communists against Fascists—is a greater threat to democracy than the frontal attack of reactionaries.” Quite a statement from a liberal beacon during a decade of fascist regimes spreading across Europe. Seldes then offers this insight regarding the publisher: “When the CIO [the Congress of Industrial Organizations] was a bright dream Stern applauded, when it became a successful reality, it scared the hell out of him.”

Indeed, the militancy of industrial strikes since 1934 was the primary source of liberal misgivings, despite the fact that they lead toward their alleged ideal—the realization of social democracy. Against the entrenched illiberalism of big business, the New Deal had produced the original “excess of democracy,” and liberals were forced to bump up against the horizon of their utopianism.

The liberal psyche inevitably harbored mistrust toward labor and the poor because, since the advent of modern liberalism, the worker had appeared as either an abstraction or a swarthy menace opposed to the liberals’ strategies of scientific management and commercial advertising. Further, were this “excess of democracy” to ever result in the power of self-determination, would the newly-minted workers even look upon liberals as their natural leaders? To the liberal mind, the likely answer was worrying.

Liberalism Redacted

It was the president’s own rapprochement with big business during the recession of 1937 that would become the north star for liberal defection from the most vaunted of their platform planks; public ownership of utilities. Roosevelt began aligning himself wholeheartedly with the commitment to exports—like Hoover before him—as the solution to contemporary economic woes. Thus, the administration tiptoed away from the “left-wing nationalism” of the first term. As Gerard Colby-Zilg reported in Dupont: Behind the Nylon Curtain, “Roosevelt had already considered the New Deal’s domestic program completed, and always dismissed any consideration of abandoning private corporate ownership in favor of nationalization and a closed economy.”

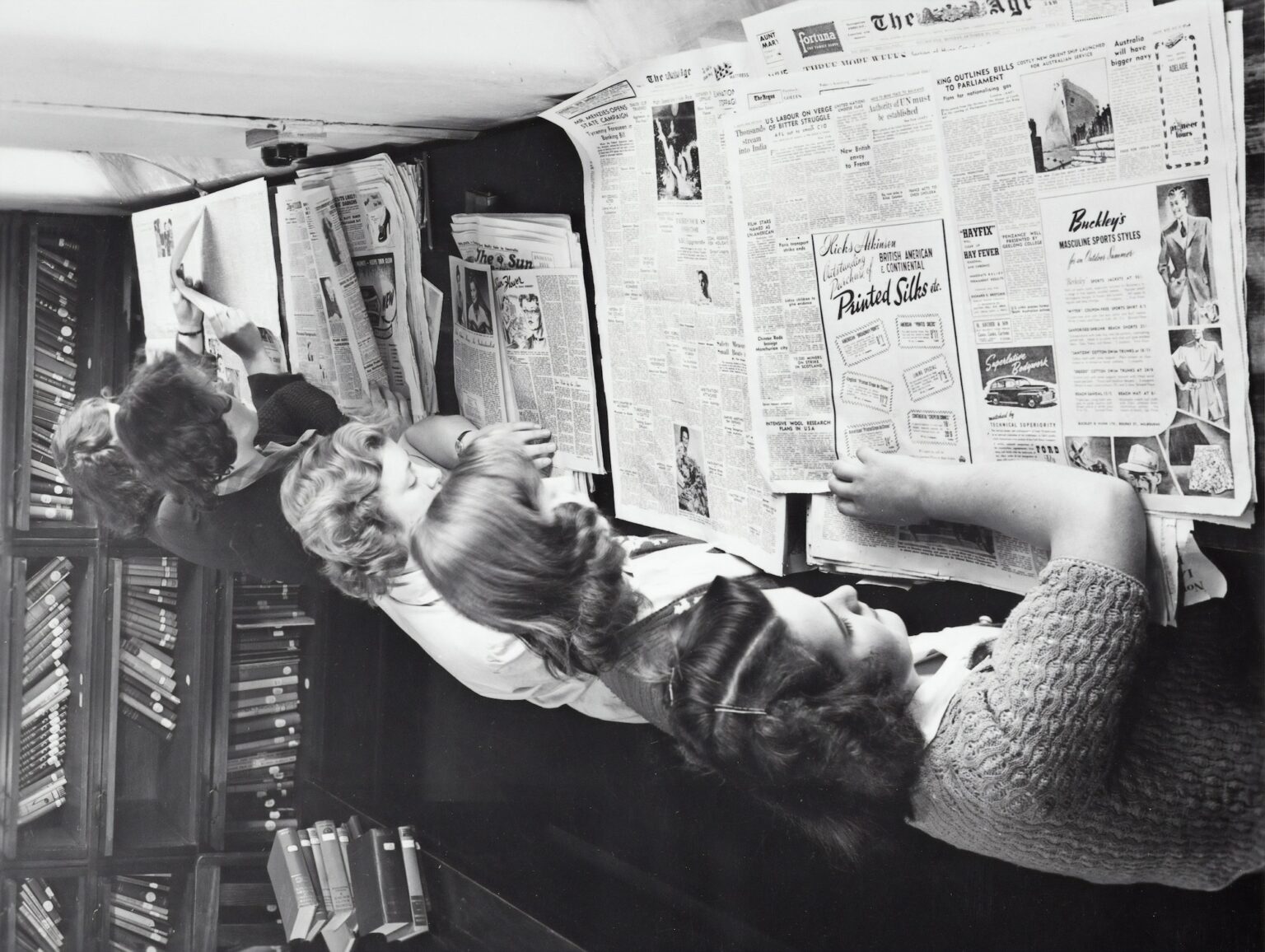

However, New Deal liberalism still had a tremendous popular cache. Seldes’ interpretation of the election as a “repudiation of the press” reveals that the climate of 1936-37 was the inverse of our current era. Americans had finally reached a critical mass in their opinion that newspapers were “biased against labor and in favor of the utilities… banks and big business.” Seldes charges the big papers in general with being frequent purveyors of “fake news” and singles out the reactionary Chicago Tribune as “a great enemy of the American people.” This moment marks the high-water mark of public consciousness, as the masses had become, however fleetingly, immune to the virulent red-baiting of the plutocrats.

To counter these prevailing winds, the National Association of Manufacturers and the utility companies enlisted reputed liberal columnists to assail the New Deal and persuade the president to make peace with the utilities. “But the type of daily columns these writers grinded out long ago destroyed any claims to liberalism they may have had,” Seldes writes, noting that until only a year before “liberals spoke for public ownership of the railroads and the public utilities.” In spite of this abrupt sea change, nearly all of these high-profile assaults on the liberal and progressive policies of the New Deal were “presented to the public as being [written by] ‘liberals.’” A coup d’état of public perception was clearly afoot in the land, and it’s crucial to stress that its goal was the denigration of whatever degree of political acumen the public had acquired throughout the 1930s.

The First “Next FDR”

Unfortunately, the stickiness of liberals toward the person of Roosevelt precluded any strategic response to the concerted efforts of big business to refine the core of liberalism. The war boom only added to the inevitable trajectory of postwar politics. Was this monomania merely the political trend of the day—Churchill, Hitler, Stalin, etc.… or was it a matter of the liberals’ unreasonable attachment to the man who had given them political oxygen? Nevertheless, those adhering to the liberalism and progressivism of the early New Deal would soon be immobilized for posterity.

Meanwhile, those carrying water for the Roosevelt team in the early 1940s began publicizing the newly sanitized liberalism, which would come to be known as the “vital center,” and whose leftward edge represented unquestioning support of the war efforts, optimism (at first) for a future of peace and cooperation with the Soviet Union and a cautious, paternalistic stance toward labor rights. If the deference liberals and progressives showed to Roosevelt in the ‘40s dulled their capacity for both strategic and critical thinking, it also signaled a desire to be insiders, and not outsiders. As historian Richard Pells writes, the editors of The New Republic “sought the attention of the powerful… but in gaining [it] they suppressed much of what they may have said.”

After Roosevelt removed progressive lodestar Henry Wallace from the ticket in 1944, The New Republic went on to “eagerly subordinate their economic and social demands to the exigencies of a reelection campaign.” So, it’s no surprise that Pells concludes, in 1989, that “they offered no convincing reason why Roosevelt should pay attention to liberal ideas when liberal loyalties were never in doubt.” Indeed, the apple never would fall far from this tree. Fearing above all the loss of influence, or prestige, they clung to the ghostly vestiges of the New Deal rather than embracing the vision of a postwar social democracy.

The full-on progressive candidacy of Wallace four years later should have offered a snug harbor for an authentic liberal movement. But it is at least circumstantial evidence of the latter’s transience as a possible alternative for American liberalism that spokesmen for the “vital center” insisted that a vote for the Progressive Party could only weaken the “movement” and allow Republican candidate Thomas Dewey to cakewalk into the White House. Despite initial excitement, Wallace fell flat, and Harry Truman was hailed as the “next FDR.”

Yet, despite the Democrats’ having wrested control of Congress from the Republicans, Truman failed to push through popular liberal policies, such as national health insurance (which he favored), and the repeal of the Taft-Hartley Act (which had defanged labor) because he was stymied by a tired coalition of Republicans and Southern Democrats. Though each copy of FDR is more faded than the last, the historical echoes are increasing their clangor.

From Past to Present

By now it should be plain that liberalism’s abandonment of the public interest occurred long before the so-called neoliberal era. It began in reaction to the awakening of public consciousness during the 1930s. There existed a mass awareness that the big papers– not journalists and the free Press– were “enemies of the people ” because their publishers aggressively advanced the interests of the plutocrats. This political savvy vindicated the wariness and mistrust with which liberals already viewed their constituents. The “vital center”, then, was sculpted in the wind tunnel of this dysfunctional relationship and decades on they have inherited from Roosevelt’s “economic royalists” the heirloom of disdain for workers and the poor.